Multiple Sclerosis and the Gut Microbiome

Exciting new studies by researchers at Harvard Medical School and the Karolinska Instituet in Sweden have looked at the links between gut health and the blood-brain barrier, and the implications this has for the role of the gut microbiome and multiple sclerosis. In this article, we will be looking at:

- What is the blood-brain barrier?

- How is the blood-brain barrier linked to multiple sclerosis

- Impact of gut microbiome on multiple sclerosis

- Best probiotic for multiple sclerosis

What is the blood-brain barrier?

The blood brain barrier is a network of blood vessels that is designed to prevent the flow of anything other than vital nutrients and hormones from the circulating bloodstream to the brain. Scientists have found that some other man-made compounds that are very small and/or fat-soluble, including antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, alcohol and cocaine are also able to slip through the endothelial cells that make up the blood-brain barrier without much effort. However, in general the barrier works as an effective ‘security patrol system’ protecting the delicate brain tissue from foreign substances.

This is an incredibly important function, and when blood-brain barrier integrity breaks down as it does with certain brain infections or some brain cancers, substances that are normally kept out of the brain can gain entry and cause a whole host of problems. It is even thought that a weakening of the blood-brain barrier may precede the onset of many neurodegenerative diseases such as MS.

How is the blood-brain barrier linked to multiple sclerosis?

An international research team, led by Swedish scientists from Karolinska Institutet have published a study1 in the journal ‘Science translational medicine’ that shows that our gut microbiota may contribute to the closing of the blood-brain barrier before birth.

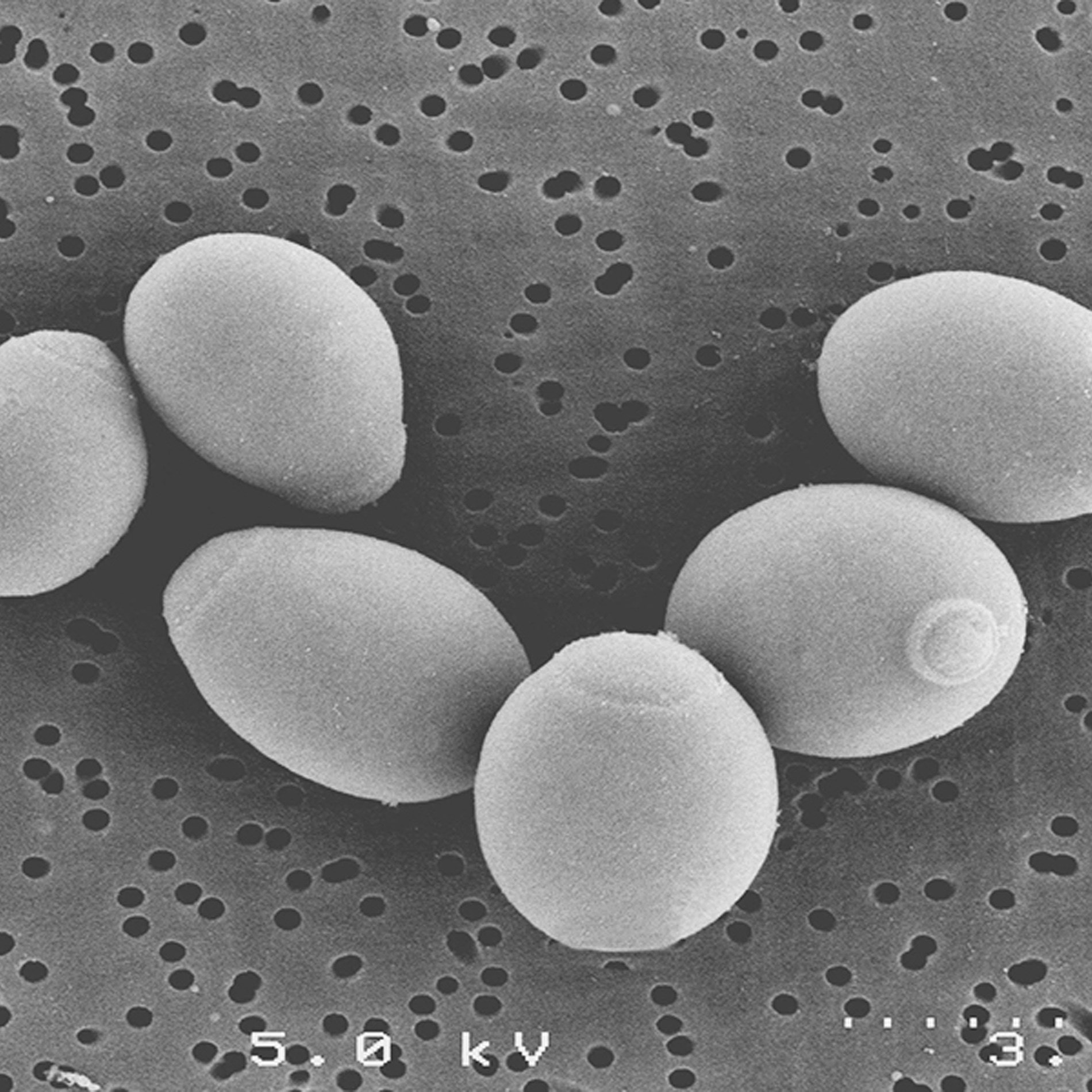

The study looked at the relationship between blood-brain barrier function and gut microbiota status in two groups of mice. The first group were raised in an environment where they were exposed to normal levels of bacteria, and the second group were raised in a sterile environment, and therefore had a completely sterile gut.

By using ‘labelled’ antibodies the scientists were able to trace the flow of substances from the general circulation into the brain parenchyma of their study subjects. Their findings showed that the ‘germ free’ mice had increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier, allowing the entry of these ‘labelled’ antibodies into the brain, and this permeability was maintained throughout the mouse’s lifespan. Although interestingly, the scientists observed that this permeability could be reversed if the mice were exposed to normal gut bacteria through a faecal transplant. The mice that were raised under normal conditions, and that therefore had a fully formed gut microbiota did not display any signs of this weakened blood-brain barrier function, and therefore did not have labelled antibodies within the brain parenchyma.

Little is understood at this time as to the exact mechanisms involved with the seemingly protective effects of gut bacteria on the blood-brain barrier. However, the researchers did observe that the tight junction proteins of the blood-brain barrier underwent structural changes in the absence of bacteria.

Impact of gut microbiome on multiple sclerosis

So does the gut microbiome impact on MS? Can there be a link between leaky gut and multiple sclerosis? Is it possible that gut bacteria and diet are significant in multiple sclerosis?

An exciting new scientific paper2, by researchers at Harvard University Medical School, does show a possible link between the gut microbiome and the rate of progression of multiple sclerosis symptoms in MS sufferers.

In MS the immune system attacks a protein called myelin, that ordinarily covers the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord allowing for smooth transmission of electrical signals. Inflammation and damage to this protective myelin sheath results in degeneration of the nervous system and an interruption of nerve impulses, resulting in a wide range of different symptoms.

The research has found that two proteins, TGF alpha and VEGF-B, are responsible for either promoting or inhibiting inflammation within the Central Nervous System (CNS). TGF alpha appears to have a protective effect on the CNS whereas VEGF-B increases inflammation. Elevated levels of VEGF-B protein are associated with excessive inflammation and cell damage, and a worsening of MS symptoms. These proteins were found to be produced in response to the breakdown of dietary tryptophan by our gut bacteria.

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that is present in many different protein foods, with good sources being: turkey, cottage cheese, eggs and various nuts and seeds.

Building on previous research, this latest study was able to illustrate that gut bacteria were involved in regulating the production of these pro- and anti-inflammatory proteins. When gut bacteria break down dietary tryptophan, they produce small molecules which then bind to receptors on nerve cells, blocking the production of the pro-inflammatory proteins VEGF-B and promoting the production of the TGF alpha anti-inflammatory proteins. The study authors were very excited by this finding, which indicates that metabolites produced by our resident gut bacteria can actually travel around the body and positively affect cells in the central nervous system. Incredible!

Best probiotic for multiple sclerosis

Dr Bruce Bebo, Executive vice president of Research at the National MS Society, which co-funded the study said: ‘It is complicated to dissect when this pathway is acting positively to suppress inflammation and promote repair, or negatively causing inflammation and blocking repair. This new research increases understanding of these pathways and is likely to lead to strategies and treatments which can slow down and even stop disability in MS.'

Despite this positive stance, Bebo did go on to caution that: ‘we are still a long way away from being able to make recommendations about diet in MS’ but Dr Francisco Quintana, lead author of the research paper adds that his research team are ‘in the process of securing intellectual property agreements and also developing potential probiotic supplements with pharma companies’.

More research is needed into these areas, however if the study findings can be replicated then the knowledge could potentially be used to develop ways of both opening up the blood-brain barrier (to enable drugs to have access to the brain) or conversely, strengthening the barrier function, which could have therapeutic effect in neurodegenerative conditions. It would be interesting if it could lead to further research in to gut health and multiple sclerosis.

It's possible that in the future there may be specific probiotic formulations that we can use to protect the brain from toxic substances leaking through the blood-brain barrier. Whether certain strains of probiotics are more effective at regulating this function thean others, is a question that will need to be answered, but we are excited to see where the research might lead. Who knows, maybe one day there will enough research to support specific probiotics and multiple sclerosis.

Head over to our Probiotics Learning Lab for more glossary terms and definitions.

To read about the role of the microbiome in other neurological disorders, such as Parkinson's Disease, you may like to read my earlier blog post.

Parkinson's Disease linked to gut bacteria

What are Psychobiotics?

References

1. Science translational medicine, Volume 6, Issue 263, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009759 ''Blood-Brain Barrier: The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice''.

2. Veit Rothhammer, et al. (2018) 'Microglial control of astrocytes in response to microbial metabolites' Quintana Nature, vol. 557: 724-728